Labour's plan to build 1.5m homes – can it be delivered?

BBC

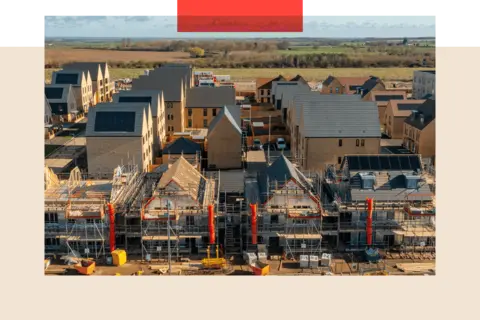

BBCThe residents of Northstowe in Cambridgeshire have been promised a thriving community. The plan is for more than 10,000 new homes for 26,000 people as part of the UK’s first new town since Milton Keynes was built six decades ago.

Six years after people first moved into the 1,480 homes built so far, there are three schools, a pub, and some other facilities – but no shops or GP surgery.

Labour has singled out Northstowe by name as part of its pledge to build 1.5 million homes over its first five years in power. At the end of August, it revealed plans for a “new homes accelerator”, which Chancellor Rachel Reeves has described as a “taskforce to accelerate stalled housing sites” like Northstowe.

It’s not just planning reforms that the government has its eye on. At the Labour conference this week, Housing Secretary Angela Rayner told the BBC she wants to see “the biggest wave of council housing in a generation and that is what I want to be measured on”.

Labour hopes its grand housebuilding push will reduce prices – something sorely needed for many young people who cannot afford to buy or rent. Relative to annual earnings, housing has not been this expensive in England and Wales for well over a century. Meanwhile, planning approvals are at the lowest number since records began in 1979.

But will Labour’s plans actually make much difference? Or does it risk making the same mistakes as the previous government? Speak to those inside the industry, and you hear concerns.

Planning reforms have limited impact

The proposed planning overhaul is what Labour has concentrated on most so far. It wants to reintroduce housing targets for councils and make it easier for developers to build on so-called “grey” parts of the green belt.

“We will soon lay out plans to speed up and streamline the planning process even more,” a housing department spokesperson told the BBC. However, planning reforms can only achieve so much – no matter how wide-ranging they are.

While Labour can change policies about which sort of sites should get planning approval and employ more people to speed up planning approvals, when it comes to putting spades in the ground, most new housing in the UK is built by a handful of large housebuilders. And the government cannot tell them when and how much to build.

If the economy is doing well and interest rates are low, housebuilders like to deliver homes because they are confident people will buy them. If interest rates are high, as they are at the moment, they tend to slow down.

PA Media/ Joe Giddens

PA Media/ Joe Giddens“The number of houses that are constructed is much more closely aligned with GDP than it is with the wishes of politicians to get them built,” says Peter Bill, a housing author and journalist.

He describes the 1.5m target as a “foolish promise” and points out that developers do not deliver a service according to how much Britons need it. Just like any other business, they do it for profit.

This explains why major housebuilders have been delivering fewer homes over the last couple of years. Earlier this month, Barratt Developments, the UK’s biggest housebuilder, posted a slump in completions in its most recent results and said it would build even fewer homes next year. It said “cost-of-living pressures, much higher mortgage rates and limited consumer confidence” were hurting housing demand.

As for Northstowe, there is frustration with the government’s suggestion that the site is “stalled” and needs a planning taskforce to “accelerate” it.

A source close to the local council pointed to recent progress – Homes England, Keepmoat, and Capital&Centric signed an agreement to deliver 3,000 homes and a new town centre at Northstowe in July – and said that the speed of delivery there depends on the market, not the planning system.

“There are no planning issues,” the source added.

Are developers to blame?

Rather than blaming the planning system, some accuse the large housebuilders of land banking – sitting on sites that already have planning permission but refusing to build on them until they feel the market conditions mean they can make maximum profit.

“One of the big issues is the monopolisation of the housing market,” says Elizabeth Bundred-Woodard, policy director at the Campaign to Protect Rural England. “The big housebuilders don’t want to flood the market because then prices would fall.”

She says that the government could tackle this by supporting smaller housebuilders, who she says tend to be supported more by local people particularly in rural areas.

The counter-argument is that the large housebuilders are “price-takers” rather than “price-makers”, because most of the homes bought and sold in the UK are second-hand.

It is the sale price of those second-hand homes rather than the whims of the large housebuilders that determine the price of homes, the thinking goes.

Getty Images/ Sean Gladwell

Getty Images/ Sean GladwellAnd developers would argue that they’re not the obstacle. A spokesperson for the Home Builders Federation (HBF), the housebuilder lobby group, described the idea of land banking as a “myth”, claiming that what’s blocking smaller housebuilders instead is “the increasing complexities, red tape, regulatory costs, and delays in the planning process”.

The Competition and Markets Authority’s (CMA) view is that “red tape” and our overdependence on big housebuilders are both at fault.

“The complex and unpredictable planning system, together with the limitations of speculative private development, is responsible for the persistent under delivery of new homes,” it concluded after a one-year study into whether the big housebuilders control the market.

In other words, though Labour’s planning overhaul could help move the dial on housing, it is unlikely to be enough.

How to fund social housing

Labour is also focusing on social housing. As well as pledging the biggest increase in social housebuilding in a generation, it aims to change Right to Buy legislation to make it easier for councils to buy or build social housing with the money they make from the sales.

“The only way you’re going to get anywhere near 1.5m homes is by pouring billions of pounds into the construction of homes for poorer people,” argues Mr Bill.

For most of the 20th Century, councils played a big role in building housing, delivering up to 80% of homes in some years, but between the 1980s and 2000s social housing delivery plummeted as governments opted for privatisation.

Today, councils deliver a fraction of new homes, with the bulk delivered by the large private housebuilders. Practically the only social housing that has been built over the last three decades has been from housing associations.

In Scotland, the picture is somewhat different. It abolished Right to Buy in 2016 because it did not want to lose the social housing it had and has delivered much more social housing relative to its population than England, Wales, or Northern Ireland in recent years. However, as with everywhere else in the UK, delivery there remains heavily dependent on private housebuilders.

Getty Images/ Justin Paget

Getty Images/ Justin PagetIf councils are given the money to build social housing, campaigners argue they will make it back in rental income. The upfront investment needed to do this could be more than expected, though, as the drive to build 1.5m homes in just five years could cause material and labour costs to soar.

And even setting aside the issue of expense, council-built housing is not a silver bullet. The lack of housing development expertise in councils means well-intentioned plans can go wrong in a hurry.

In 2014, Croydon council set up a company called Brick by Brick, which it said would deliver affordable housing for its residents. Instead, the company collapsed seven years later, with a council report attributing this to "shortcomings in the governance".

Auditors said the failed venture was one of the reasons Croydon fell into bankruptcy in 2021. The council would go on to declare bankruptcy two more times.

“The poor performance of the company, combined with governance failings, contributed to the council’s current debt position of £1.4bn on the general fund,” a spokesperson told the BBC, adding: “The council has since worked tirelessly to limit the losses incurred.” Croydon sold off the final Brick by Brick property in June.

Partnerships with private developers

There is another way. In Northstowe, the housing quango Homes England is partnering with the private sector. The idea is that the government can cut down on its own costs while also benefiting from industry expertise.

It is also what the Mayor of London is trying to achieve with the private developer Pocket Living. Together, they are building blocks of flats where all the homes meet the official definition of affordable – 80% of market value – for both rent and sale.

One of their flagship projects is in Croydon.

Paul Rickard, managing director of Pocket Living, believes the government needs to do more to help smaller companies like his, which could help address concerns about a housebuilding monopoly.

“If the SME sector is not supported, it is going to go extinct,” says Mr Rickard, pointing out that the previous government spent billions on the Help to Buy scheme, where it effectively gave first-time buyers cash grants at the point of purchase.

He says the government could instead redirect that money towards social housing. “You can’t have subsidised housing without subsidy,” he says.

Partnership has its faults too, though. While Pocket Living homes meet the official definition of affordable, 80% of market value is still out of reach for many people.

Mr Rickard calculates that two decades ago when the developer started building, around 40% of its target market could afford Pocket Living homes. Now, he thinks the figure is less than 8%.

Some homes have been built that are more affordable, with prices based on local incomes rather than market value, which Pocket Living can deliver because of its “relatively low margins”.

However, the company still has to consider what makes sense from a business perspective. “There comes a point where a scheme is just not deliverable,” says Mr Rickard.

In short, there are downsides to all of the standard housing delivery ideas: changes to the planning system only do so much, social housing costs money, and private developers need to make a profit.

Are we too intent on building?

Others have suggested that a single-minded focus on building 1.5m homes over the next five years is not the right approach to solving the housing crisis. For example, a report from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) published in March recommends the government and councils buy homes from landlords to let them out at much cheaper rents.

This, too, would cost money, but the JRF says councils would make this back from rental income and from the money saved not relying on landlords to house its most vulnerable through temporary accommodation – something that is already costing councils billions.

The JRF says this could supplement existing social housing development, and it would help to give millions of people a cheaper place to live, which is ultimately the issue at the heart of the housing crisis.

Ideas like these remain on the fringes of policymaking, and Labour will likely still need to deliver new housing in places such as Northstowe where homes can be built at scale to address the housing crisis. But solutions such as those from the JRF show the range of options available. The millions of Britons who cannot afford to buy or rent their own homes may thank the government for thinking outside the box.

Clarification 8 October 2024: This article has been amended to add that Right to Buy has been abolished in Scotland.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.