The UK's unique, circular hike where accommodation is just £20

Sarah Baxter

Sarah BaxterNine churches on the 60-mile Golden Valley Pilgrim Way have opened their chancels, crypts and cloisters to pilgrims of all faiths – or none.

As my eyes adjusted to the half-light filtering through the stained-glass window, I met a pair of eyes staring back. Blank eyes; lifeless, stone cold. I rolled over, away from the impervious gaze of the chiselled face. There was the silent organ, the empty nave. I inhaled deeply: the fusty smell of knelt-on hassocks; well-thumbed hymnals; centuries of damp, dust and prayer.

It had been a comfortable night at St Faith's church in the English village of Dorstone. There was no ensuite. Nighttime calls of nature meant unlocking the heavy door with a giant iron key ripped from a fairytale and dashing to the "Chapel of Ease" (a portaloo in the graveyard). But the blankets and hot-water bottle had made the camp bed cosy. And the atmosphere was divine.

I was following Herefordshire's Golden Valley Pilgrim Way, a 60-or-so mile loop from Hereford Cathedral into the English county's south-west, via the churches of Abbeydore Deanery, sleeping in a different one each night. Still active places of worship, they've opened their chancels, crypts and cloisters to pilgrims of all faiths – or none. A per-night donation of £20 per person generates much-needed revenue – Church of England statistics show that church attendance has more than halved since 1987, and 641 churches have closed altogether since 2000. It also secures a unique, low-cost spot for walkers to rest.

Launched in 2021, The Golden Valley Pilgrim Way was the brainchild of Reverend Simon Lockett, a rural pioneer priest in the Hereford diocese. He was inspired by making his own pilgrimage on Italy's St Francis Way. "It was seriously life-changing," he confessed. "But it was also a celebration – of the food, the culture, the art. I stayed in monasteries and rooms at the back of churches. And I thought: we should be doing this."

Sarah Baxter

Sarah BaxterDesigning the route was easy. "I just linked the churches and the pubs," Lockett said. Though it helps that it weaves through wonderful walking terrain, hemmed between two river valleys and Wales's broad-backed Black Mountains, an area that feels time-warped and untouched. It's hard to believe, given how serene western Herefordshire seems now, that it was once tumultuous border country, a battleground for power struggles between Welsh princes and the English crown; a place of medieval warfare and shifting alliances, its soil soaked in blood.

Unusual for a pilgrimage, the route is circular. "People can come by train or bus and don't have to get back to a car," Lockett explained. "Also, there's something in coming back to where you started, but coming back changed."

How to visit

The Golden Valley Pilgrim Way begins and ends in Hereford. "Night sanctuary" is available at nine churches along the route, plus Hereford Cathedral cloisters. Pilgrims must bring sleeping bags and pillows. Facilities vary but are basic; access to a sink and toilet is guaranteed. A donation of £20 per person per night is requested. Book via abbeydoredmc@gmail.com.

I started in Hereford where, since 2023, it's been possible to overnight in Hereford Cathedral's 15th-Century Vicars Cloisters; it's believed to be the first cathedral in Britain to house pilgrims since medieval times. After finding my room, with its assemble-yourself camp bed, tea tray and kettle, I attended evensong. The voices of the choir soared clear and true in this acoustically peerless nave, home to a choir since at least the 13th Century. It gave me the shivers.

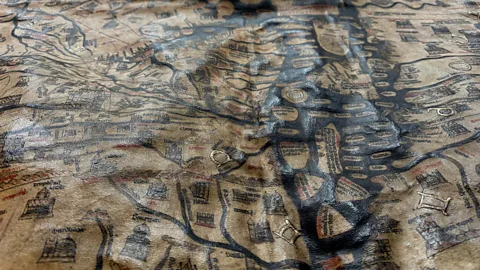

Hereford Cathedral was once a major place of pilgrimage, with devotees flocking to the shrine of St Thomas Cantilupe, a former Bishop of Hereford, canonised in 1320. The shrine remains, though nowadays more visitors come for the cathedral's Mappa Mundi, the largest surviving medieval world map, drawn on a single piece of vellum. Jerusalem sits in the middle, east is at the top, Britain bottom-left, strange beings all around: unicorns, cynocephali (dog-heads), men with faces in their bellies. "One theory is that this was placed near Cantilupe's shrine," volunteer Vivian told me as I peered at the map's phantasmagoria. "It might have been to attract more paying visitors."

Sarah Baxter

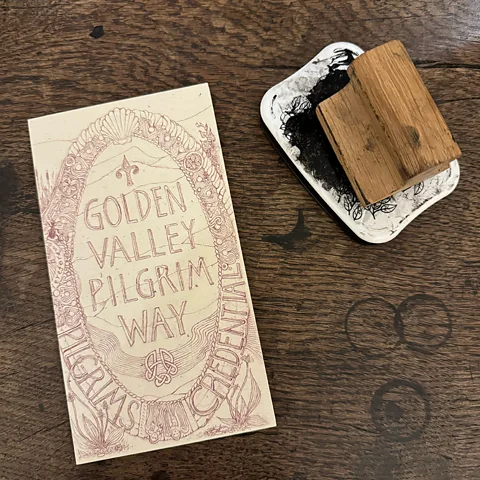

Sarah BaxterIt was certainly an attraction rather than a navigational tool, and I was pleased to have downloaded digital GPX map files to my phone to direct my own pilgrimage as I set out from the cloisters on a crisp March morning, bells ringing me out of town and along the River Wye. I was bound for Dorstone via lanes, footpaths and a succession of churches, in many of which I could stamp my credential, the paper passport issued to all pilgrims.

The first stamp was in Madley, an overly impressive church for such a small village, and the only one on the route to have real pilgrim pedigree. St Dubricius was born in Madley – this 6th-Century saint and scholar is said to have been a founder of Orthodox monasticism in Wales and allegedly went on to crown King Arthur. Later, a statue of the Virgin Mary kept here was believed to have special powers. Now, pilgrims can sleep in the restored medieval crypt where the statue was once displayed. Though I'd advise bringing long johns – it was chilly down there.

The rest of the day brought primroses and daffodils, the 800-year-old oaks of Moccas Park and Arthur's Stone, a Neolithic burial chamber in the hills above the Golden Valley. Below lay Dorstone, and St Faith's, my home for the night. Here, church contact Nick Gethin came to check I was okay, asking if there was anything I needed or anything more they could provide, and the 12th-Century Pandy Inn served a huge, hot supper, perfect for weary pilgrims.

Over the following three days I looped through the Herefordshire countryside, my feet revealing the land in a way no other mode of transport can. I was sensing the soul of the place through the soles of my boots, from its castle mounds – reminders of border strife – to its solemn graveyards, a life story on every stone. Indeed, sleeping in churches thrust me into every community's historic heart, surrounded by the residents of centuries ago, and those who live here still.

Sarah Baxter

Sarah BaxterThis was made clearest in valley-tucked Clodock, a village almost in Wales but feeling far from anywhere at all. The 12th-Century church of St Clydawg's shares a wall with the Cornewall Arms, one of a dying breed of old parlour pubs that are more like your granny's living room than a public tavern. It had no music, food nor even a proper bar, but there was a serving hatch, skittles table and a high-backed wooden settle to sit on by the crackling fire. The Cornewall was designed for socialising – and overnighting at the church proved a good conversation starter. I soon fell to chatting with the landlady's brother, who grew up in the pub. Had it changed since he was a child, I asked? "Not really," he replied. "Though there were seven pubs and cider houses within a mile and a half back then."

More like this:

• An epic 38-mile hike to England's northernmost point

• A new chance to hike Europe's ancient salt route

• A three-day canoe trip into Scotland's sublime borderlands

The number of inns may have diminished, but hospitality is still key to this pilgrim trail. Lockett was keen that his route not only provide spiritual sustenance but showcase local produce too, passing pubs, village stores, ice cream churners and cider makers – "I was interested in how something like this might help maintain communities," he said.

Happy to oblige, I made the most of the area's offerings, from stocking up at Hopes of Longtown – purveyors of everything from lemon drizzle to gaffer tape – to buying meat pies at Mailes in Ewyas Harold, a family butcher established in 1892. And, after a long day up-downing from Clodock to Kingstone, via Dore Abbey's magnificent remains, I was grateful that Bill Giles was on call.

Giles is warden of Kingstone's St Michael & All Angels Church and, for a small fee, can make meals for pilgrims. No sooner had I schlepped into the nave, mud-soaked and foot-sore, a home-cooked shepherd's pie appeared. "We're the Hilton of the Golden Valley!" Giles exclaimed, not unreasonably. The church has a fully equipped cafe-kitchen and a toilet befitting a boutique hotel, albeit floored with old memorial stones.

Sarah Baxter

Sarah Baxter"If you look at the history of churches, they did everything," Giles told me, brandishing a sticky toffee pudding. "They didn't have pews. You could do all sorts of things in them. That's what we want to get back to."

After a restful night, I walked the final miles back to Hereford, mulling on Giles' words, and Lockett's too. "Pilgrims are real searchers," he'd told me. "And in all cultures there's the idea of the vision quest. It isn't an individualistic thing. You go out and bring something back for the community."

The Golden Valley Pilgrim Way, with its thickets and swards, its streams, springs and high, windswept places, is a route for silence and contemplation. And it not only feeds the souls (and bellies) of its wandering pilgrims, but also benefits the churches and locals among whom they roam.

Slowcomotion is a BBC Travel series that celebrates slow, self-propelled travel and invites readers to get outside and reconnect with the world in a safe and sustainable way.

--

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news, delivered to your inbox twice a week.