'You have to destroy in order to create' – How the Sex Pistols sparked outrage

Getty Images

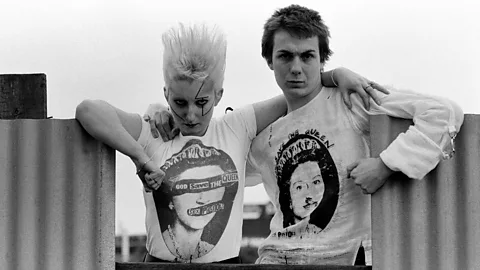

Getty ImagesWith its provocative title and lyrics that openly attacked the UK establishment, on this day in 1977 the Sex Pistols' God Save The Queen sparked outrage with its release. Six months earlier, the BBC tried to get to the bottom of the chaotic youth movement that seemed to be challenging the very foundations of British society.

On 27 May 1977, during the patriotic run-up to the 25th anniversary of Queen Elizabeth II's accession to the throne – the punk group The Sex Pistols released an incendiary single that ignited a firestorm of controversy and brought them overnight notoriety.

Warning: This article contains language some readers may find offensive

The song, God Save the Queen, was a searing critique of the monarchy and the established political order it represented. Powered by stripped-back guitars, raw energy and furiously scathing lyrics, it proclaimed that the Queen "ain't no human being", people had "no future" and the UK was "a fascist regime".

The record, and the timing of its release just before the Silver Jubilee, seemed a very direct challenge to the traditional reverence afforded to the monarch at the time. Within days, the BBC had rushed to issue a total ban on its radio and TV airplay.

BBC Radio Two controller Charles McLelland branded the song as "gross bad taste", while Labour MP Marcus Lipton denounced it, saying "if pop music is going to be used to destroy our established institutions, then it ought to be destroyed first".

Many shops, like Woolworths, simply refused to stock the single.

The Sex Pistols had emerged as part of a punk movement that was rapidly spreading in the UK in the mid-1970s, as the country grappled with economic stagnation, rising unemployment, power blackouts and bubbling racial tensions.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith its DIY spirit and anti-authority stance, punk was a response to boredom, social conformity and alienation that many young people felt. The music that came out of it articulated the hypocrisy that they saw in both the British establishment and UK's mainstream culture.

Unapologetic, unruly and confrontational, The Sex Pistols, personified this punk ethos.

Six months before the single's release, in November 1976, one such establishment institution, the UK's national broadcaster, the BBC, had invited the band in to be interviewed on current affairs programme, Nationwide.

The broadcaster was keen to get to grips with a cultural movement reflecting the anger, frustration and disillusionment that seemed prevalent among the nation's youth and which was so clearly worrying its older viewers.

The band at the time was made up of singer Johnny Rotten (aka John Lydon), guitarist Steve Jones, drummer Paul Cook and bassist Glen Matlock, who would leave the following year to be replaced by Sid Vicious. They were introduced with a segment that aimed to bring the audience up to speed with what they described as "the cult of punk".

"Well, it may not be the best rock 'n' roll in the world, but it is certainly the most controversial," intoned a clearly disapproving voiceover from presenter Lionel Morton, which warned viewers that one London newspaper had called the Sex Pistols "the most aggressive, nasty band ever".

His co-presenter Maggie Norden, who was actually much younger than the band's manager Malcolm McLaren, also seemed to struggle to understand the appeal to so many young people of this visceral, nihilistic garage rock and the band's contempt for authority. She put it to McLaren that they were "more into chaos than anything else".

"Well, that's an accusation by people who really don't understand what kids want," said McLaren.

"Kids want excitement, they want things that are going to transform what is basically a very boring life for them right now, and music, young rock music, is the only thing they have, that they thought that they controlled. And if you look in the charts, they don't really have anything to do with it."

'Worthless, nasty'

Norden took the band to task – saying that "they were trying to shock everyone" – as well as calling their clothing "bizarre" and asking Johnny Rotten if he was happy with the term punk, saying it meant "worthless, nasty".

"The press gave us it. It's their problem, not ours. We never called ourselves punk," he replied enigmatically.

She went on to press them on what was wrong with bands of the 1960s who were still going, like The Rolling Stones and The Who, which she seemed more comfortable with as a sound of teen rebellion.

Johnny Rotten merely dismissed them as being established, saying: "They just do not mean anything to anyone."

BBC's Nationwide had also brought in music journalist Giovanni Dadomo, who at the time wrote for music papers Sounds and ZigZag, to challenge the band.

He accused their music as being "a bit derivative", and the Pistols' attitude as being "boring".

"Destruction for its own sake is dull, ultimately," said Dadomo. "You know it doesn't offer any hope, it doesn't really want to change. It's just saying, 'we don't like this, we're different, look at us'."

McLaren countered: "You have to destroy in order to create, you know that. You have to break it down and build it up again in a different form."

It is uncertain how sincere Dadomo was himself in his own view, since the following year he would go on to form and front his own punk rock group called The Snivelling Shits.

More like this:

McLaren was defiant in his belief that the band would overcome the concerted resistance from the music business, the media and the political establishment, believing young people had the power to change public opinion.

"It won't be the journalist, it won't really be the music industry. It will be the kid on the street because he's the guy who buys the record," he said.

"Does it matter if the record doesn't sell?" Norden asked.

"There's no question it'll sell," McLaren said in response.

He was talking about the Sex Pistols' debut single, Anarchy in the UK, which would make it to number 38 in the UK singles chart. That record would also end up being banned from BBC airwaves after the band's controversial and sweary appearance on the TV programme Today descended into chaos.

In History

In History is a series which uses the BBC's unique audio and video archive to explore historical events that still resonate today. Subscribe to the accompanying weekly newsletter.

This time, however, the attempts to suppress God Save the Queen only served to fuel its popularity. The record flew off the shelves in the shops that did stock it, climbing the charts to number two. It was denied the top spot, somewhat ironically given its banned status, by a song titled I Don't Want to Talk About It by Rod Stewart.

This led to allegations that the single chart had been manipulated to stop the Pistols reaching number one, which was seen by punks as yet more evidence of the establishment's efforts to quell dissent.

And for all the questions during the BBC's Nationwide interview about dangerous behaviour at the Sex Pistols' gigs, it was band members or those associated with their songs who were subject to violence. Following the outrage generated by the record, on 19 June 1977, Johnny Rotten and the song's producers, Chris Thomas and Bill Price, were attacked with razors outside a pub in Highbury, London. The drummer, Paul Cook, was assaulted by six men armed with knives outside Shepherd's Bush tube station on the following day.

On 7 June, less than two weeks after God Save the Queen's release, the band chartered a boat to go down the River Thames, defiantly performing the song as they cruised past the Houses of Parliament. The Sex Pistols invited music journalist Allan Jones on their boat trip and to see them play live.

"Of course, when they did God Save the Queen, I mean that boat could have imploded. It was just amazing," he told the BBC in 2012.

But it would be short-lived. The police forced the boat to dock, resulting in a fight and 11 people, including McLaren, getting arrested.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe controversy, and the bans, would not end for the band with God Save the Queen.

Their debut album Never Mind the Bollocks, released later the same year, was also swiftly banned by major retailers Woolworths, Boots and WHSmith. And it triggered an obscenity trial after a Virgin Records shop manager in Nottingham was arrested for displaying its "indecent printed matter" album cover, the work of designer Jamie Reid.

Just three months following the album's release, the Sex Pistols broke up following a calamitous and chaotic US tour.

But the band's impact reverberated far beyond their brief career, and God Save the Queen, with its ragged musicality, has lost none of its potency, remaining an embodiment of the anti-establishment spirit of punk.

"The song has lost none of its power over the intervening years," Jones told the BBC in 2012.

"The emotions behind the song, the sense of defiance, rebellion are still entirely relevant and it will still sound more exciting than anything else that's in the charts at the moment."

--

For more stories and never-before-published radio scripts to your inbox, sign up to the In History newsletter, while The Essential List delivers a handpicked selection of features and insights twice a week.