Gardi Sugdub: The Americas' disappearing island

Adri Salido

Adri SalidoFor more than 100 years, the Indigenous Guna people have lived on a tiny Caribbean island. Now, they're poised to become some of the Americas' first climate change refugees.

Set some 1,200m off Panama's northern coast in the San Blas archipelago, the tiny Caribbean island of Gardi Sugdub (sometimes written Cartí Sugdub) is home to nearly 1,300 members of the Indigenous Guna community. After surviving Spanish colonisation in the early 1500s, it is believed that a combination of factors (including disease, venomous snakes and clashes with other Indigenous groups) led the Guna to settle along a series of 49 islands as well as a strip of coastline in what is now the Guna Yala autonomous region in the 19th Century.

But after inhabiting this 400m-by-150m island for more than 100 years, Gardi Sugdub's residents will soon be forced to abandon their island home – and that's because the island may soon disappear under the sea.

Since the 1990s, residents on the densely packed island have noticed that their thatched- and tin-roof homes are flooding more and more, especially during the November-to-February rainy season. According to the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, the sea around Gardi Sugdub is now rising 3.4mm per year (more than double the rate during the 1960s). Since most of the Guna-inhabited islands lie only 0.5m to 1m above the water, "it is almost certain that all the islands will have to be abandoned by 2100," said Steve Paton, the director of the Institute's oceanographic monitoring programme.

As sea levels continue to rise, the same ocean that has historically helped to preserve the Guna's culture, language and colourful mola clothing is threatening its very survival. Yet, unlike other Guna communities affected by climate change, the residents of Gardi Sugdub have a plan. In 2010, the island's leaders began working with the Panamanian government to develop a new village on the mainland from which they once fled. Known as Isber Yala, the planned community is being built by the islanders on land they already own.

At first glance, Isber Yala couldn't be more different from Gardi Sugdub: instead of tightly packed wooden and metal houses facing the sea, the new community is comprised of prefabricated concrete homes set several kilometres from the ocean. Families are scheduled to begin relocating from the island to the new community in February 2024, and when they do, the Guna will be among the first climate refugees in the Americas.

Adri Salido

Adri SalidoThe 365 islands that comprise the San Blas archipelago are renowned for their beauty and are mostly uninhabited. Gardi Sugdub is by far the most densely populated of the 38 islands and 11 mainland communities where the Guna live. To reach Gardi Sugdub (whose name means Crab Island in the native Guna language), you can either drive 110km north-east from Panama City to the coastal settlement of Cartí or take a short flight to the Cartí airport. From there, the only way to arrive on the island is via a boat-taxi operated by local Guna members, which operate every few hours.

Adri Salido

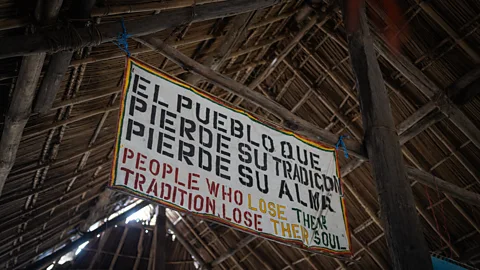

Adri SalidoWhether building dugout canoes to fish in the surrounding sea or paddling to the mainland to harvest building materials, the Guna have developed a unique cultural identity that's inextricably linked to their environment. According to Blas López, one of the community leaders involved in the construction of Isber Yala, being evacuated from Gardi Sugdub could disrupt the islanders' culture. "Now, after [hundreds of] years, the community of [Gardi] Sugdub is going to move and this will have an impact on them, so a process of adaptation will be necessary for the people in this new environment," he said.

Adri Salido

Adri SalidoWhen Panama gained its independence from Colombia in 1903, the Guna (who had historically straddled the Colombia-Panama border) were divided and Panama's nascent government embarked on a campaign to "civilise" the Guna. The forced assimilation was intended to rid the Guna of their language, dress and traditions, but the Guna resisted. This resistance culminated on 25 February 1925 when the Guna declared their independence. Though this revolution, known as La Revolución Dule ("The Dule Revolution", referring to the word the Guna use to call themselves: "Dule" or "People") barely lasted a week, it initiated a peace agreement that allowed the Guna to maintain their traditions and granted them a level of political autonomy they enjoy to this day.

Adri Salido

Adri SalidoOne of the most important elements of this autonomy is the saila (a political and religious leader) who oversees each Guna village from a Congress House. "The Congress House, called Onmaket Nega in the Guna language, is a fundamental element for our community. It has enormous cultural value and is [where] the population is summoned to discuss social and community problems. It also has a fundamental spiritual and Indigenous worldview, since this is where the saila transmits all [Guna] ancestral knowledge through songs," said López. "It is a place where harmony with nature is taught, with the sea, the forests and all the elements that make up us [Guna] as an Indigenous community."

Adri Salido

Adri SalidoThe Guna inhabiting the San Blas archipelago have historically made their livelihoods off fishing – and were even known to provide seafood to some of the finest restaurants in Panama City. But in recent years, as access to the Pan-American highway has improved, rising sea level and overcrowding on Gardi Sugdub has intensified and the destruction of nearby coral reefs has accelerated, fishing has become more challenging. As a result, many islanders have turned to tourism. Some now transport tourists with their taxi-boats from the mainland to Gardi Sugdub and other nearby islands, while others have opened small restaurants and modest lodgings on nearby islands where tourists can stay overnight surrounded by idyllic landscapes. There is even a tiny museum on Gardi Sugdub dedicated to Guna culture.

Adri Salido

Adri SalidoTraditional Guna clothing is quite striking, especially in the case of women who wear traditional garments called molas whose vibrant prints are inspired by the flowers, birds, reptiles and plants that inhabit the Guna Yala region. According to some historians, molas come from an earlier time when the Guna painted their bodies to scare away spirits. This paint completely covered one's front, back and sides, because the Guna believe that the Universe is made up of different levels in which there is no empty space.

It usually takes between 60 and 80 hours to hand-sew each cotton mola, and the reverse applique method of layering each design is traditionally taught by mothers to daughters. Since the Panamanian government actively tried to eradicate molas prior to The Dule Revolution, they remain an important symbol of the Guna's identity and autonomy.

Adri Salido

Adri Salido"I have been quite affected by the rise in sea levels because I live near the water, so every time the tide rises, the water enters my home," said Magdalena Martínez, who owns a small convenience store on Gardi Sugdub. "This is something that has always happened here, but recently it has been occurring in a much more violent way."

Adri Salido

Adri SalidoRising sea levels isn't the only reason Gardi Sugdub is becoming uninhabitable. According to a report by Human Rights Watch, the island was nearly half its current size when it was first settled, but over the years residents have taken the surrounding coral reefs, garbage, rocks and cement blocks to expand the landmass. While this "filling" practice has helped create more space on the island (whose highest point is just 1m above the sea) the destruction of the coral reefs that historically buffered it from storms has also left it more susceptible to erosion and flooding. Furthermore, since there is no proper sewage system, most human waste ends up in the ocean, which causes diseases for those who swim in it.

Adri Salido

Adri SalidoDespite years of "filling", Gardi Sugdub now faces a huge population density problem, as it has become impossible to build more houses. Hygienic and sanitary conditions are also poor as the island doesn't have reliable access to clean water. An underwater water pipe reaches Gardi Sugdub, but it frequently runs dry, leaving residents to paddle to a river on the mainland to get fresh water. And while some residents proposed relocating the community to a larger nearby island, studies have shown that rising sea levels are affecting the entire archipelago to such an extent that by 2050, scientists believe many others near Gardi Sugdub won't be inhabitable.

Adri Salido

Adri Salido"We are all affected in one way or another by the rise in sea level, because every time it rains and the sea level rises, our house looks like a swimming pool and we sleep on top of that pool. For the future of the community, it is better for us to move inland, although in my opinion, I don't know if that is going to be the solution because in a few years the water may even reach the new community. Furthermore, I also believe that this is a problem that not only affects our community, but also affects the entire Guna Yala región," said Dalys Morris, a schoolteacher on Gardi Sugdub.

Adri Salido

Adri SalidoAfter years of delays, Isber Yala's 300 homes are finally expected to be completed in February 2024, at which point families are supposed to begin evacuating the island. According to López, there is still a lot of work to do – including creating a water sanitation system – and he remains sceptical that Isber Yala will be inhabitable next month. Still, with each prefabricated house designed to have electricity and access to clean drinking water, and the community equipped with a health centre and a brand-new Congress House, Isber Yala could provide the residents of Gardi Sugdub the one thing they currently lack: a secure future.

BBC Travel's In Pictures is a series that highlights stunning images from around the globe.

---

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for The Essential List newsletter – a handpicked selection of features, videos and can't-miss news delivered to your inbox every Friday.