Bosnia and Herzegovina's mysterious 'stećci' stones

stu.dio/Alamy

stu.dio/AlamyMore than 60,000 vividly rendered tombstones dot the nation's countryside and offer a fascinating glimpse of medieval life in the region.

Whenever I travel through Herzegovina, the southern part of my homeland Bosnia and Herzegovina, I go to a large field 3km west of the town of Stolac called the Radimlja necropolis. There, I come face to face with 135 medieval tombstones arranged in densely concentrated rows. As I marvel at the geometric patterns, moons, stars and people seemingly greeting me with outstretched hands etched onto the white stones, I wonder who is buried there and how they lived. This isn't just any cemetery; it jealously guards hundreds of years of my country's history.

Called stećci (pronounced" "stech-tsee"), these monolithic tombstones are some of Bosnia and Herzegovina's most recognisable – if enigmatic – landmarks. Some 60,000 of these medieval stone monuments lie scattered across the nation's countryside (with a much smaller number found in neighbouring Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro), and are commonly grouped together in necropolises. Emerging from the greenery of the Bosnian hills and meadows, their vividly rendered designs have been puzzling historians and travellers for centuries, but continue to serve as a symbol of national pride and identity among Bosnia's multi-ethnic population.

Stećci were made from the 12th to the 16th Centuries, and like gravestones elsewhere in the world, they are sometimes decorated with religious crosses and rosettes. Others show weapons, which could indicate the social status and profession of the deceased. Scenes of stag hunts, chivalry duels and circular group kolo funerary dances all offer fascinating glimpses of daily life in medieval Bosnia.

Davor Vukovic/Alamy

Davor Vukovic/AlamySome stećci have Cyrillic inscriptions containing information about the deceased, as well as philosophical remarks, such as the Viganj Milošević epitaph, which reads: "I once was as you are and you shall be as I am." These inscriptions reveal telling details about literacy levels of the time.

The word stećci (which is the plural of stećak) comes from the verb stajati, which means "to stand" because their purpose was to stand over the grave of the deceased and identify her or him. Due to their historical and cultural significance, stećci have been inscribed on the Unesco World Heritage List for their "outstanding universal value".

According to the director of the History Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Elma Hašimbegović, one of the most interesting aspects of stećci is how they represent "the intertwining and merging of different influences – Eastern and Western, Mediterranean, Byzantine and Central European, Catholic and Orthodox, [and] the influence of Latin and Cyrillic literacy".

Throughout history, the territory of modern-day Bosnia and Herzegovina has been a meeting place of various cultures and religions. The Orthodox, the Catholic and the Bosnian church (a medieval church that existed between the 12th and the 15th Centuries) coexisted in medieval Bosnia, and many scholars agree that stećci were used by followers of all three religious groups, based on the Eastern Orthodox-inspired crosses and rosettes found on stećci, the Western-inspired motifs of a shield with sword, and certain inscriptions translating as, "(a person) of true Roman faith" or "slave of God".

Olivier Wullen/Alamy

Olivier Wullen/AlamySome experts believe that stećci were created by the Bogomils, a dualistic religious sect originating in the Balkans. A less-popular theory links them with the Vlachs, a nomadic population that lived in the Balkans at the time. Interestingly, since anthropologists began studying stećci at the end of the 19th Century, Serbians, Croatians and Bosniaks (the three ethnic groups that comprise most of Bosnia and Herzegovina today) have all tried to claim stećci as their own.

Hašimbegović described this as typical for historically "divided societies" such as those in Bosnia and Herzegovina, which, she said, "views culture and cultural-historical heritage exclusively through the prism of national politics and identity". But as many stećcihave been neglected over the years, Hašimbegović had a message for political leaders: "Let them appropriate [stećci], but let them also take care of this World Heritage."

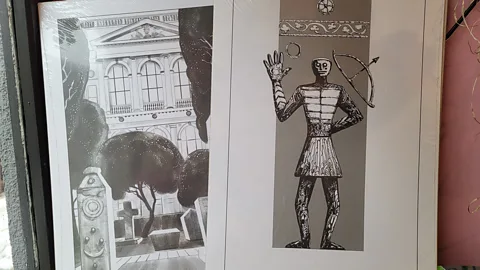

Among the best-preserved and most valuable of these World Heritage sites is Radimlja. The site's most famous symbol – as well as the first image that comes to mind for most Bosnians and Herzegovinans when they think of stećci – is a depiction of a male figure etched on one of the necropolis' tombstones, raising his right hand while his left clutches a bow and arrow. Some anthropologists think it could represent a gesture of prayer to the Sun or Moon.

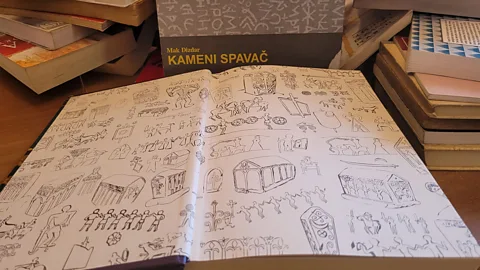

The motif of the raised hand is also common in the work of the Bosnian poet Mehmedalija Mak Dizdar, who grew up near Radimlja. "Stone Sleeper", his 1966 masterpiece, was inspired by stećci drawings and inscriptions, and is considered one of the most significant literary works in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Dizdar's poems reawakened Bosnians and Herzegovinians to the importance of these stones, and remind us to honour our past while embracing our identity.

Lidija Pisker

Lidija PiskerAs a result, stećci – an in particular, the raised hand – have come to embody the Bosnian spirit of cultural openness. Today, the image elicits an emotional connection for many Bosnians and Herzegovinians.

Following in the footsteps of Dizdar, younger Bosnian Herzegovinian artists have recently begun to explore stećci and incorporate them into their works. Sculptor Adis Elias Fejzić interprets the nation's present and the future by looking at its past. "I don't know what the creators of ancient stećci saw in their stones and wanted from them, but I know what I see in them. That's why I'm reviving that tradition after several centuries [by sculpting them]," Fejzić said.

One of Fejzić's stećak-like sculptures stands in front of Australia's Parliament House in Canberra, as a gift from Bosnia and Herzegovina to Australia. Another was erected in Odense, Denmark, at the request of Bosnian Herzegovinian refugees living there. The majority of his works, however, are in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

"With stećci, I am most directly connected to our Bosnian and artistic origins," Fejzić said. "The stećak is also a 'time machine' with which I communicate so easily and quickly in my own perception and creativity with traditions and styles from [our past]."

stu.dio/Alamy

stu.dio/AlamyStećci have also inspired the works of award-winning illustrator and designer Aleksandra Nina Knežević, who has made illustrations for books and other projects based on the tombstones. "What I find very inspiring and attractive about stećci is that the motifs that appear (on them) celebrate love, life, joy and a generally positive attitude," Knežević said. "This reveals the sensibility and desires of the people of that time, our ancestors, and says a lot about our heritage, our character and our nature."

Knežević is far from alone. Another young artisan using stećci to embrace his cultural heritage is coppersmith Denis Drljević, whose AbrakaBakra Copper Art shop is located in Mostar's Old Town. "I started using motifs from stećci from the very beginning of my practice of this craft," Drljević said. "They represent one of the oldest artefacts of our history." Last year, Vedrana Božić, who runs the Mostar art and craft gallery Claire Noel, started selling fashion bags with her paintings of stećci printed on them: "I love the mix of tradition and modernity, and I wanted to present our cultural heritage in a modern way," she said.

Besides illustrations, copper reliefs and bags, travellers can now purchase stećak-inspired women's jewellery, decorative pins, T-shirts and other souvenirs honouring the country's medieval past.

Historian Gorčin Dizdar (the grandson of the famous poet) wrote a book about stećak and also promotes Bosnian and Herzegovinian culture through his Mak Dizdar Foundation. One of the Foundation's recent projects was to gather young people from across the nation to compile an interactive Stećak Map in order to identify previously unregistered stećci and digitise already-known ones.

Lidija Pisker

Lidija PiskerWhile Dizdar, local artists and younger Bosnians are embracing stećci as a source of pride, many of these necropolises remain neglected by local authorities. Radimlja, for example, is on the list of endangered national monuments because an industrial and commercial zone was built in the immediate vicinity.

The media often report on cases of damage to stećci and their deterioration. Three years ago, an online ad from a Bosnian hoping to sell an alleged stećak near his house triggered strong public reactions. Some condemned him, while others condemned the government's negligence in protecting these sites.

But as more and more of the public is reawakening to the value of these mysterious medieval relics, the hope is that a growing grassroots movement can spur authorities to better preserve them.

"I think that it is a very positive trend because in this way, younger generations and individuals who are not necessarily interested in medieval art, encounter this very valuable element of our cultural heritage," Dizdar said.

--

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.