Owamni: A (r)evolution of indigenous foods

Dana Thompson

Dana ThompsonThrough The Sioux Chef, Sean Sherman and Dana Thompson use food as a guidepost to a hidden part of history, all while sparking a (r)evolution of "true" North American foods.

On the back patio at Owamni – the Minneapolis, Minnesota, restaurant owned by Sean Sherman and Dana Thompson – the late-evening sun cast my dessert in a natural spotlight. Marigold-coloured agave squash caramel cascaded slowly down the sides of a sunflower-seed cake the colour of sandstone, and a deep red berry sauce shimmered atop a maple chaga cake so earthy in tone, it felt as though it were plucked from the forest floor.

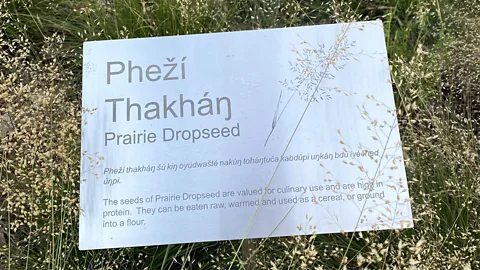

The connection to nature is palpable here, where sweeping views of the Mississippi River, along with curated indigenous plants like prairie dropseed – whose high-protein seeds can be eaten raw or ground into a flour – etch themselves into the landscape like a painting.

"We named this restaurant Owamni from the Dakota name OwamniYomni, for the waterfall that used to surround this area," said Thompson, a descendant of the Wahpeton Sisseton and Mdewakanton Dakota tribes. "It was said to be as beautiful as Niagara Falls. Spirit Island was the most sacred of the four islands here, and the Dakota and Anishinaabe communities would take their canoes there for ceremony, and women would come from far away just to give birth there."

Thompson's grandfather, who contributed historical knowledge to the book Where the Waters Gather and the Rivers Meet, an atlas of the Eastern Sioux published in 1994, made it possible for this important piece of indigenous history to live on.

One of Owamni's many strengths is its ability to bridge the past to the present, knowing one can only exist because of the other. You feel this in the dining room, perched on the second floor of two abandoned flour mills, restored after the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board and Parks Foundation raised more than $19 million to honour the indigenous history of the area by creating a park with Owamni as its inspiration. It's an investment that has already paid off in powerful ways.

Less than a year after opening in July 2021, Owamni was named 2022's Best New Restaurant in the United States by the James Beard Foundation – whose annual awards recognise exceptional talent in the culinary arts, hospitality, media and the broader food world. The accolade is big deal for any restaurant, but a monumental one when a decolonised menu is on the table. At Owamni, this means never using ingredients introduced to North America after Europeans arrived – including cane sugar, wheat, dairy, pork and chicken. Instead, only indigenous ingredients like turkey, bison, walleye, beans, wild rice, mushrooms, sweet potatoes, herbs, maple syrup and blue corn are featured.

Other ingredients – like crickets, acorns and timpsula (or prairie turnip) – might be unfamiliar to more mainstream American palates, despite coming from the places we walk, cycle and drive past. But eating the food here brings with it a profound sense of place difficult to put into words.

Dana Thompson

Dana ThompsonWhile I've had sunflower seeds and honey before, I never expected that, with the addition of water, such simple ingredients could become a cake befitting any pastry shop. And though I can only imagine what a molten sunset absorbing a field of pumpkins into its hot, sticky flow would taste like, I feel certain nothing would come closer than the ethereal squash-agave caramel painted on top. It was so addictive I could have eaten an entire bowl of it. But then I wouldn't have had room for the blue corn mush – a hazelnut and berry porridge – from the Ute Mountain Ute tribe in Colorado. A pool of maple syrup lay in wait at the bottom of the dish, and its sweetness, combined with the tender grit of the corn meal, the crunch of the hazelnuts and soft, tart berries, felt like a hug from my grandma.

And that glistening berry topping on the maple chaga cake? It's a Lakota berry soup called wojape, which Sherman uses as a sauce in both sweet and savoury dishes. As a child, he'd gather buckets full of fresh chokecherries to make it but uses many different berries today.

The food, while beautiful, is so much more than a plate of art. It's a thoughtful entry point for conversations about indigenous history – something inherent to the mission of The Sioux Chef, the company Sherman, an Oglala Lakota chef, founded in 2014, and co-owns with Thompson. Their business started with catering and pop-ups and now includes a food truck, the non-profit North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems (NATIFS) – from which the Indigenous Food Lab, a professional indigenous kitchen and training centre in Minneapolis' Midtown Global Market is based – and, of course, Owamni. The wheels are already in motion to replicate the Indigenous Food Lab across the country, with immediate plans for locations in Montana and Alaska, and, eventually, into more than 45 satellite locations across the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia and South America.

Stefanie Ellis

Stefanie Ellis"North America's history begins with indigenous history," Sherman said. "There should be Native American restaurants all over the place."

While he and culinary cohorts – like James Beard finalist Crystal Wahpepah, chef Nephi Craig of Café Gozhóó in Arizona, cook and educator Hillel Echo-Hawk and I-Collective co-founder Neftali Duran – have long been working to shift the conversations around indigenous food, the cuisine is still just gaining a foothold in the US.

Recognising the limited time they have to capture guests' attention, Owamni brings the past to life with intentional design touches – from a map that hangs in the foyer, noting the original indigenous names for the waterways and villages throughout Dakota Territory, to the sunlight-flooded dining room, whose wall of windows gives guests a clear view of the pulsing river below.

At the door, a neon sign reminds you: You Are on Native Land. Thompson asked if I'd like to pose under it for a photo and snapped away on my iPhone. Though she and Sherman know some people still favour trendy food photos over the story behind the food, they're banking on the fact that the more exposure people have to indigenous culture, the more they'll want to learn its history.

Stefanie Ellis

Stefanie EllisBut what that history is and isn't makes their work all the more challenging.

"History books were written by the US government," said Sherman. "You always hear how Native Americans died from starvation and disease, but people were intentionally mutilated, murdered and killed brutally.

"When you follow American history, you'll see that from 1800-1900, indigenous people still had [access to] over 80 percent of land [in the US], but by the end of that century, had access to just two percent."

He pointed to a shockingly long list of historical events systematically designed to stamp out indigenous culture, such as the US government's massive slaughtering of buffalo. Before 1800, an estimated 60 million buffalo roamed the land, offering crucial food sources, along with material for shoes and clothing, housing, cooking vessels and medicine. By 1900, after widespread efforts eradicated the buffalo population across the country, only a few hundred animals were left, effectively paralysing the mechanisms that existed for indigenous people to maintain a self-sustaining way of life.

In his cookbook, The Sioux Chef's Indigenous Kitchen, Sherman explains that fry bread – often the only thing people associate with Native American food – is "a difficult symbol connecting the present to the painful narrative of our history. It originated [nearly 155 years ago] when the US government forced our ancestors from the homelands they farmed, foraged and hunted, and the waters they fished. Displaced and moved to reservations, they lost control of their food and were made to rely on government-issued commodities – canned meat, white flour, sugar and lard. Fry bread contributes to high levels of diabetes and obesity that affect nearly one-half of the Native population living on reservations. Obesity and tooth decay did not exist among indigenous people of North America before colonial ingredients were introduced."

Stefanie Ellis

Stefanie EllisSherman, who grew up on South Dakota's Pine Ridge Reservation, says these historical events devastated so much for human beings and their knowledge base, yet no one is talking about it.

"It's not ancient history," he said. "This just happened."

Every culture has its own connection to food, including how it's prepared, grown and consumed. For indigenous people, food sovereignty – the right to healthy and culturally appropriate food and the right to define food and agriculture systems – was erased through colonisation. Sherman hopes to put the power back in the hands of the people, because he believes when you control your food, you control your destiny.

In North America, ingredients like the tepary bean, a culturally appropriate food and an important heirloom crop brought back from near extinction by Ramona Farms in Arizona, grow abundantly in areas without a lot of water. And at Owamni, when mixed with salt, sunflower oil, pepita meal and maple syrup, it creates an immensely comforting foundation for the tender tumble of smoked Lake Superior trout (from the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa in Wisconsin) piled on top. The fish was remarkable – evoking memories of a snuffed-out campfire that left the tiniest trail of smoke lingering in the air, catching you off guard when you walk past.

The duck sausage, served with roasted turnips and a watercress puree, was succulent and elegant, notes of maple whispering on the palate. It was the perfect companion to a bowl of tender and nutty hand-harvested wild rice – actually the seed of an aquatic grass – with dried currants and root vegetables.

Dana Thompson

Dana ThompsonThe natural world was always a connective thread in Sherman's life. Even in the year he spent after high school working as a field surveyor for the US Forest Service, identifying plants and trees in South Dakota's Black Hills National Forest – whose name comes from the Lakota words, Paha Sapa, meaning hills that are black – he said memories coded into his DNA began to unlock.

"We know the names of more Kardashians than we do trees," Sherman said. "Plant knowledge is power. Everything has a purpose. Even poisonous plants, if used correctly, can be medicine."

Mexican inspiration

The roasted, skin-on sweet potatoes with indigenous chilli crisp served at Owamni are inspired by Sherman's time in Mexico. "There'd be this guy who came around with steamed sweet potatoes he served with chili and lime," he recalled. "His cart whistled as he came down the street. I liked that combo of sweet and spicy. I harvest chillies in my own garden to make this using maple sugar, dried chiles, sunflower oil and salt."

Most of his career was focused on restaurants – bussing tables, washing dishes, learning to make pasta, studying wine and, eventually, becoming an executive chef at 29. In 2008, he took a year off from his job rebuilding the restaurant program for a large fitness corporation, and moved to the village of San Pancho in Nayarit, Mexico.

"I saw so many commonalities between the way the indigenous Huichol people in my village were living, and how I grew up, and realised I didn't know much about my Lakota ancestry," he recalled. "I started researching everything I could find, and the more history I learned, the more important this work became. I wanted to open up doors to something that has been very hidden, and I can do that through food. We all have a connection to it as humans, and it's a gateway to understanding other cultures."

While Sherman won the James Beard Awards for Leadership in 2019 and for Best American Cookbook in 2018, this year's best new restaurant honour opens more space for conversations about history, privilege and the continued fight for a seat at the table.

"It's a game changer," he said. "Typically, it's saved for high-end restaurants for very privileged people – European chefs making European foods. Not much diversity has gone into that award, so to stand out in a crowd like that and get the attention we need to pull off what we're doing, is incredible."

"There's a lot of damage in our history, and a lot of healing that needs to be done, but we have to start somewhere. What we're doing is just a little step into something much larger."

Thompson sees the impact of their work mirrored by the community. "The staff, city, other business owners, Native community, people who come with their roller bag from the airport who didn't make a reservation – it's this organism now," she said. "People are truly invested in this existing."

And while Sherman admits that a restaurant is perhaps one of the worst business plans you can come up with, he also believes one restaurant can change an entire community.

"We're just trying to take as much knowledge from our ancestors and creating spaces to learn – working backwards to start to reclaim it so that we have a true (r)evolution of indigenous foods," he said. "Our restaurant is just showing what's possible, and I think it's proving its point."

Dana Thompson

Dana ThompsonMixed Berry Wojape (makes about 2-4 cups)

Owamni by The Sioux Chef

Ingredients:

1 cup water

1 pinch mineral salt [such as sea salt]

1 cup blackberries

1 cup blueberries

1 cup raspberries

1 cup strawberries, tops removed

2 tablespoons maple syrup

Instructions:

- Bring the water to a simmer in a medium saucepan; add the salt and the berries.

- Let simmer for 20 to 30 minutes, continuing to stir as the berries break down. Cook to yourdesired consistency.

- Remove from the heat and stir in the maple syrup.

BBC.com's World's Table "smashes the kitchen ceiling" by changing the way the world thinks about food, through the past, present and future.

---

Join more than three million BBC Travel fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

If you liked this story,sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter called "The Essential List". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.