If we made contact with aliens, how would religions react?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe discovery of life on another planet might seem incompatible with faith in a deity. Yet many theologians are already open to the existence of extraterrestrials, argues the writer Brandon Ambrosino.

In 2014, Nasa awarded $1.1M to the Center for Theological Inquiry, an ecumenical research institute in New Jersey, to study “the societal implications of astrobiology”.

Some were enraged. The Freedom From Religion Foundation, which promotes the division between Church and state, asked Nasa to revoke the grant, and threatened to sue if Nasa didn’t comply. While the FFR stated that their concern was the commingling of government and religious organisations, they also made it clear that they thought the grant was a waste of money. “Science should not concern itself with how its progress will impact faith-based beliefs.”

The FFR’s argument might well be undermined, however, when the day comes that humanity has to respond to the discovery of aliens. Such a discovery would raise a series of questions that would exceed the bounds of science. For example, when we ask, “What is life?” are we asking a scientific question or a theological one? Questions about life’s origins and its future are complicated, and must be explored holistically, across disciplines. And that includes the way we respond to the discovery of aliens.

This is not just an idle fantasy: many scientists would now argue that the detection of extraterrestrial life is more a question of when, not if.

There are several reasons for this confidence, but a main one has to do with the speed at which scientists have been discovering planets outside of our own Solar System. In 2000, astronomers knew of about 50 of these ‘exoplanets’. By 2013, they had found almost 850, located in over 800 planetary systems. That number may reach one million by the year 2045, says David Weintraub, associate professor of Astronomy at Vanderbilt University, and author of Religions and Extraterrestrial Life. “We can quite reasonably expect that the number of known exoplanets will soon become, like the stars, almost uncountable,” he writes. Of those discovered so far, more than 20 are Earth-size exoplanets that occupy a “habitable” zone around their star, including the most recently discovered Proxima b, which orbits Proxima Centauri.

The upshot is that the more we’re able to peer into space, the more certain we become that our planet isn’t the only one suitable for life.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith few exceptions, most of the discussions about Seti (the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence) tend to stay in the domain of the hard sciences. But the implications of Seti extend well beyond biology and physics, reaching to the humanities and philosophy and even theology. As Carl Sagan has pointed out in (the now out-of-print book) The Cosmic Question, “space exploration leads directly to religious and philosophical questions”. We would need to consider whether our faiths could accommodate these new beings – or if it should shake our beliefs to the core.

Working out these questions might be called exotheology or astro-theology, terms defined by Ted Peters, Professor Emeritus in Theology at Pacific Lutheran Theological Seminary, to refer to “speculation on the theological significance of extraterrestrial life”. As he notes, Peters isn’t the first or only one to use the term, which dates back at least 300 years, to a 1714 publication titled ‘Astro-theology, or a Demonstration of the Being and Attributes of God From a Survey of the Heavens’.

How unique are we?

So what issues might the discovery of intelligent aliens raise? Let’s start with the question of our uniqueness – an issue that has troubled both theologians and scientists. Guiding Seti are three principles, as Paul Davies explains in the book Are We Alone? First, there’s the principle of nature’s uniformity, which claims that the physical processes seen on Earth can be found throughout the Universe. This means that the same processes that produce life here produce life everywhere.

Second is the principle of plenitude, which affirms that everything that is possible will be realised. For the purposes of Seti, the second principle claims that as long as there are no impediments to life forming, then life will form; or, as Arthur Lovejoy, the American philosopher who coined the term, puts it, “no genuine possibility of being can remain unfulfilled”. That’s because, claims Sagan, “The origin of life on suitable planets seems built into the chemistry of the Universe.”

The third, the mediocrity principle, claims that there is nothing special about Earth’s status or position in the Universe. This could present the greatest challenge to the major Abrahamic religions, which teach that human beings are purposefully created by God and occupy a privileged position in relation to other creatures.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn some ways, our modern scientific world was formed by the recognition of our own mediocrity, as David Weintraub notes in the book Religion and Extraterrestrial Life: “When in 1543 C.E. Copernicus hurled the Earth into orbit around the Sun, the subsequent intellectual revolution … swept the discarded remnants of the Aristotelian, geocentric Universe into the trash bin of history.”

The Copernican revolution, as it would later come to be understood, laid the groundwork for scientists, like Davies, to eventually claim that ours is “a typical planet around a typical star in a typical galaxy”. Sagan puts it even more startlingly: “We find that we live on an insignificant planet of a humdrum star lost in a galaxy tucked away in some forgotten corner of a universe in which there are far more galaxies than people.”

But how could a believer reconcile this with their faith that humans are the crowning achievement of God’s creation?. How could humans believe they were the apple of their creator’s eye if their planet was just one of billions?

The discovery of intelligent aliens could have a similar Copernican effect on human’s self-understanding. Would the discovery make believers feel insignificant, and as a consequence, cause people to question their faith?

I would argue that this concern is misguided. The claim that God is involved with and moved by humans has never required an Earth-centric theology. The Psalms, sacred to both Jews and Christians, claim that God has given names to all the stars. According to the Talmud, God spends his night flying throughout 18,000 worlds. And Islam insists that “all things in the heavens and on the Earth” are Allah’s, as the Koran says, implying that his rule extends well beyond one tiny planet. The same texts are unequivocally clear that human beings are special to God, who seems fairly able to multitask.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSecond, we don’t reserve the word “special” only for unrepeatable, unique, isolated phenomena. As Peters says, the discovery of life elsewhere in the Universe would not compromise God’s love for Earth life, “just as a parent’s love for a child is not compromised because that child has a brother or sister”. If you believe in a God, why assume he is only able to love a few of his starchildren?

Revelation

But do the religious texts themselves mention the possibility of alien life? “What is most basic in religion,” writes Catholic priest and theologian Thomas O’Meara, “is the affirmation of some contact within and yet beyond human nature.” For Jews, Christians, and Muslims, this involves a written revelation, albeit one that is contingent upon the specific historical situations in which they initially circulated. The best theologies recognise these limitations. Some don’t, however, and for those believers that adhere to them, the discovery of ETs might prove initially threatening.

Weintraub thinks Evangelicals might have a difficult time with Seti, because they approach their Scriptures with a high degree of literalism. Their hermeneutical heritage extends back to Luther’s Sola Scriptura, a Reformation rallying cry that affirms “Scripture alone” is necessary for understanding God’s plan for salvation. (One notable exception here is evangelist Billy Graham who in 1976 told the National Enquirer he “firmly” believed God created alien life “far away in space”.) These believers maintain that any other writing or idea must be evaluated and judged by the Bible. Take, for example, Darwin’s theory of evolution, which some Evangelicals reject on the grounds that the Bible says God created the world in seven days.

The worldview of these believers might be summed up in the Christian slogan, “God said it, I believe it, that settles it!” Were you to ask one of these Christians if she believed in ET life, her first instinct would probably be to consider what the Bible says about God’s creation. Not finding any positive affirmation of alien life, she might conclude, like creationist Jonathan Safarti, that humans are alone in the Universe. “Scripture strongly implies that no intelligent life exists elsewhere,” he wrote in an article in Science and Theology News. Granted, she might remain open to the discovery of alien life, but she’ll have to revise her notion of divine revelation in one very big way: by tempering it with some epistemic humility.

Second, she would have to deeply reflect on the concept of the Incarnation, the Christian belief that God was fully and uniquely present in a first-century human called Jesus of Nazareth. According to Christianity, salvation can be achieved only by Jesus’ death and resurrection. All paths to God, in effect, go through him. But what does that mean for other civilisations whirling around out there in the Universe, completely unaware of Jesus’ story?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThomas Paine famously tackled this question in his 1794 Age of Reason, in a discussion of multiple worlds. A belief in an infinite plurality of worlds, argued Paine, “renders the Christian system of faith at once little and ridiculous and scatters it in the mind like feathers in the air”. It isn’t possible to affirm both simultaneously, he wrote, and “he who thinks that he believes in both has thought but little of either.” Isn’t it preposterous to believe God “should quit the care of all the rest” of the worlds he’s created, to come and die in this one? On the other hand, “are we to suppose that every world in the boundless creation” had their own similar visitations from this God? If that’s true, Paine concludes, then that person would “have nothing else to do than to travel from world to world, in an endless succession of deaths, with scarcely a momentary interval of life”.

In a nutshell: if Christian salvation is only possible to creatures whose worlds have experienced an Incarnation from God, then that means God’s life is spent visiting the many worlds throughout the cosmos where he is promptly crucified and resurrected. But this seems eminently absurd to Paine, which is one of the reasons he rejects Christianity.

But there’s another way of looking at the problem, which doesn’t occur to Paine: maybe God’s incarnation within Earth’s history “works” for all creatures throughout the Universe. This is the option George Coyne, Jesuit priest and former director of the Vatican Observatory, explores in his 2010 book Many Worlds: The New Universe, Extraterrestrial Life and the Theological Implications.

“How could he be God and leave extra-terrestrials in their sin? God chose a very specific way to redeem human beings. He sent his only Son, Jesus, to them… Did God do this for extra-terrestrials? There is deeply embedded in Christian theology… the notion of the universality of God’s redemption and even the notion that all creation, even the inanimate, participates in some way in his redemption.”

There’s yet another possibility. Salvation itself might be exclusively an Earth concept. Theology doesn’t require us to believe that sin affects all intelligent life, everywhere in the Universe. Maybe humans are uniquely bad. Or, to use religious language, maybe Earth is the only place unfortunate enough to have an Adam and Eve. Who is to say our star-siblings are morally compromised and in need of spiritual redemption? Maybe they have attained a more perfect spiritual existence than we have at this point in our development.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs Davies notes, spiritual thinking requires an animal to be both self-conscious and “to have reached a level of intelligence where it can assess the consequences of its actions”. On Earth, this kind of cognition is at best a few million years old. If life exists elsewhere in the Universe, then it’s very unlikely that it’s at the exact same stage in its evolution as we are. And given the immense timeline of the existence of the Universe, it’s likely that at least some of this life is older, and therefore farther along in their evolution than we. Therefore, he concludes, “we could expect to be among the least spiritually advanced creatures in the Universe.”

If Davies is right, then contrary to popular works of literature like The Sparrow, humans won’t be the ones teaching their star-siblings about God. The education will go quite the other way.

Let’s note that this possibility doesn’t invalidate Earth religions’ claims of divine revelation. There is no need to imagine that God reveals the same truths in the same way to all intelligent life in the Universe. Other civilisations could understand the Divine in their own myriad ways, all of which could be compatible with each other.

Identity

But what about the divisions between faiths? How would the discovery influence religious identity? A 1974 story by Phillip Klass, On Venus We Have a Rabbi!, invited Jews, and all religious people, to consider this question. At some point in the future, goes the story, the Jewish community on planet Venus holds the Universe’s first Interstellar Neozionist Conference. In attendance are an intelligent alien species named Bublas, who have traveled from a faraway star named Rigel. The Jews at the conference are bewildered by the physical appearance of the Bulbas, what with their gray spots and tentacles. They decide the Bulbas can’t really be human, and therefore they can’t be Jewish.

A Rabbinical court is called to think about how Jews should respond to their new visitors. What happens, they ask, if some day humans come across alien creatures who want to be Jewish? “Do we say, no, you’re not entirely acceptable?”

The rabbis conclude that isn’t a good response, and suggest a paradoxical way for the Venusians to look at it: “There are Jews – and there are Jews. The Bulbas belong in the second group.”

The comedy of the story is heightened by what we recognise as a certain tribalism inherent to religion. The announcement of any identity has the potential to split the world into groups: us and them. But when religion is involved, that separation takes on a cosmic dimension: us and them, and God is on our side. This has always been one of the challenges of cross-cultural conversion, which is often tasked with negotiating, though not dissolving, such boundaries.

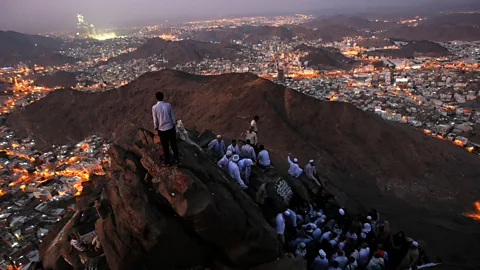

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPerhaps this is a bigger challenge to Judaism and Islam than it is for some forms of Christianity, which place less emphasis on daily rituals than other religions. Think of Islam, which requires its adherents to take up embodied behaviors throughout the year. Unlike Christianity, whose founder eradicated the necessity of location for religious experience, Islam is a very placed religion. Prayers are said facing Mecca, at five specific times throughout the day, and are physicalised through bowing and kneeling. Fasting is required at specific times, as is a pilgrimage to Mecca for all Muslims who are able. Judaism, too, has its own fasts, and – though it’s not a requirement – a concept of pilgrimage, which is its birthright trip, taglit, to the Holy Land. Contemporary Judaism, however, is not as dependent on location as Islam, given its tragic history with exile and diaspora.

What, then, would it take for an alien to be considered a participant in an Earth religion? What would she be required to do? Pray five times a day? Perhaps her planet does not rotate exactly as ours, and her days are much shorter – would she be expected to pray as often as Muslims on Earth? Would she have to be baptised? Receive communion? Build a tent for Sukkot? Though we imagine aliens to have a similar physical structure to us, there’s no reason to believe they have physical bodies. Maybe they don’t. Would that restrict their conversion options?

This may seem to be a bit of frivolous exotheology, but the point is this: all of our religious identities are Earth-centric ones. There’s nothing wrong with that (so long as we don’t collapse the Universe down to our finitude). Here’s how Rabbi Jeremy Kalmanofsky puts it: “Religion is the human, social response to transcendence … Normative Judaism provides an excellent, time-tested path for sanctifying our minds, morals, and bodies, refining us as a people, improving the world, correlating our lives to the infinite God unfolding on the finite Earth.”

His upshot? “I am Jewish. God is not.”

The rabbi’s theory can help us think about our neighbours in outer space, and our neighbours right here on this planet. If religion is a human response to divinity – even if that response is taught and initiated by divinity – then it’s obvious that those responses would differ according to the contexts in which they take shape. If Western Christians can learn to respect the religious experiences of good-willed aliens who are in their own ways responding to the divine, maybe they’ll be able to apply the same principles as they learn to live more peaceably with Muslims on Earth. And vice versa.

“In a billion solar systems,” writes O’Meara, “the forms of love, created and uncreated, would not be limited. Realisations of divine life would not be in contradiction with each other or with creation.”

The end of religion?

If we wake up tomorrow morning to the news that we’ve made contact with intelligent aliens, how will religion respond? Some believe that the discovery will set us on a path the end goal of which will be to outgrow religion. One notable study conducted by Peters found that twice as many non-religious people than religious people think that the discovery of alien life will spell trouble for earthly religion (69% to 34%, respectively).

But it’s ahistorical to assume that religion is too weak to survive in a world with aliens. That’s because, as Peters points out, this claim underestimates “the degree of adaptation that has already taken place.” With few notable exceptions – creationism, violent fundamentalism, gay marriage – religion has often been able to adapt without much fuss to various paradigm shifts it’s encountered. Surely its re-inventiveness, its adaptability is a testament to the fact that there is something about religion that resonates with humans at a basic level.

Certain aspects of religion will have to be reconsidered, but not totally abandoned, as O’Meara notes. “If being and revelation and grace come to worlds other than Earth, that modifies in a modest way Christian self-understanding” – and, we might add, all religious self-understanding. However, he says, “It is not a question of adding or subtracting but of seeing what is basic in a new way.”

Many religions have always believed God names the stars. Is it really a stretch to believe God names the stars’ inhabitants, too? And that they might possibly each have their own names for God?

--

Brandon Ambrosino has written for the New York Times, Boston Globe, The Atlantic, Politico, Economist, and other publications. He lives in Delaware, and is a graduate student in theology at Villanova University.

Join 700,000+ Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, Google+, LinkedIn and Instagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.