The space submarine hunting the solar system for aliens

BBC/Frances Breckerleg

BBC/Frances BreckerlegScientists are designing a submarine to explore the mysterious methane seas of Saturn's moon Titan.

Among all the spacecraft designed to explore the Solar System, this one may be the coolest yet. It's not a lander or a rover, but a submarine – a vehicle with an instantly recognisable torpedo shape. But unlike any other submarine, this one is designed to explore the depths of extraterrestrial seas.

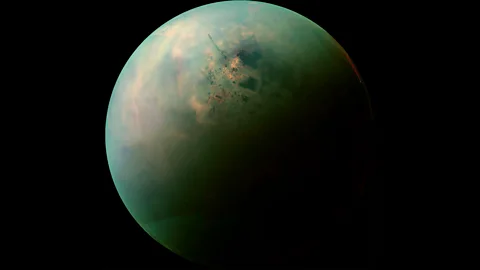

The destination is Titan, Saturn’s largest moon and the only other place in the Solar System with lots of liquid pooling on its surface. While Earth’s seas are water, Titan’s are filled with a mixture of methane and ethane – stuff that’s normally a gas on a warmer Earth. Titan is so cold – about -180C (-292F) – that these compounds are in liquid form, creating wet environments that could maybe, just maybe, harbour life.

The prime candidates for alien abodes would be Titan’s several dozen lakes and seas, the biggest being Kraken Mare. No one is quite sure how deep it is, but it likely plunges for hundreds of metres and spans as much as 400,000 square km – five times larger than Lake Superior in North America. And it’s where scientists want to send the Titan sub.

It’s unlikely that we will find alien fish swimming in Kraken Mare. But there could be microorganisms. In its hunt for habitability, the submarine would be diving into uncharted waters (or, rather, methane), exploring an alien world in a completely different way.

NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/University of Idaho

NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/University of IdahoThe first and only spacecraft to land on Titan was the European Huygens probe, which, during its descent in 2005, gathered data on the atmosphere and clouds. It snapped the first pictures of the surface. For more than a decade, Nasa’s Cassini spacecraft has been studying the Saturnian system and Titan, probing its seas with radar and collecting basic data about the liquid surface. But their depths remain unexplored.

“We don’t know what else is in there,” says Steve Oleson, an engineer at Nasa’s Glenn Research Center who’s leading the sub’s design effort. “We could send a boat, but think about when people first explored our oceans. They had no idea what’s beneath the surface.”

The submarine is still just a concept. Last year, researchers finished the first stage of designing what such a vehicle might look like. So far, they’ve come up with a six-metre-long vessel that would spend 90 days traversing 3,000 kilometres of Kraken Mare, cruising at an average speed of just 1km/h. But that ability to explore many locations and environments is a submarine’s big advantage. The Mars Opportunity rover, in contrast, has gone fewer than 45km – and it’s been operating for 12 years.

The sub would survey the sediments that settled on the sea floor, and sample how the chemistry of the sea may be changing with depth. It would study the weather and the shorelines, searching for signs of sea level change and clues about Titan’s climate history. It would probe the chemistry and geology of a world that, in certain ways, is more similar to Earth than any other place in the Solar System.

Titan and Earth are the only two Solar-System worlds where rain (albeit methane rain for Titan) falls onto the surface, filling lakes and seas that are connected by rivers and tributaries. Unlike, for example, Mars’s wispy atmosphere or Venus’s crushingly thick layers of gas, Titan’s atmospheric pressure is only about one-and-a-half times greater than Earth's at sea level.

“It’s basically the same as the bottom of a municipal swimming pool,” says Ralph Lorenz, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins University and the leading scientist of the project. “In principle, a human being could walk around on the surface of Titan with a very thick parka and an oxygen mask.”

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute

NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science InstituteBut what lies beneath is especially tantalising. Life as we know it requires liquid water, and scientists think you need some sort of liquid – like liquid methane – to coax life into existence.

“As to whether this could work or not, this is one of those problems where no amount of thinking and doing theory is going to solve,” says Jason Barnes, a planetary scientist at the University of Idaho who isn’t involved with the Titan submarine project. “We need to go there and make the measurements and do the experiments to find out.”

One way is to search for life-affirming chemical patterns. For example, the molecular building blocks of proteins, called amino acids, have structures that can be mirror images of each other. An amino acid can be left- or right-handed, Lorenz explains, and those associated with life on Earth all happen to be right-handed. The hypothesis is that any organisms in Titan seas would’ve evolved one or the other, and finding a preponderance of right- or left-handed amino acids could suggest life, Lorenz says.

The plan is for the submarine to explore Titan alone. But researchers may consider sending an orbiter to relay data and communications back to Earth. The team also needs to flesh out how the sub will get there. For now, they envision putting the sub onboard a mini space shuttle like the Boeing X-37 space plane. Titan’s atmosphere is thick enough that the craft can glide down onto Kraken Mare. It’ll then submerge while releasing the floating sub.

And there are still engineering challenges. For example, nitrogen is dissolved in the seas, like the carbon dioxide in a can of Coke. The concern is that the warmth from the submarine’s radioactive-isotope power supply will cause the nitrogen to fizz. “If it bubbles even a little bit, the bubbles can build up and interfere with our science,” Oleson says.

But there's plenty of time to figure it all out. If the sub comes to fruition, it won’t launch until around 2040, splashing down on Kraken Mare in the mid 2040s – during the Titan summer, when the sun is up all day and there’s a direct line of communication to Earth. Then, finally, it’s time to set sail.

Join 500,000+ Future fans by liking us on Facebook, or follow us on Twitter, Google+, LinkedIn andInstagram.

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.